Good to know

A simple guide to retirement planning

Why planning your retirement is vital?

Life has a habit of disappearing quickly. It seems the older you get, the faster time goes. After a busy working life, juggling family and work commitments, and trying to squeeze in some personal goals and interests, reaching retirement can bring a sense of relief… or it can bring a feeling of trepidation.

The time before retirement is the time to re-evaluate what is important in your life and to plan ahead, dedicating your available time and financial resources towards the things that really matter to you. Being proactive about how you manage time and money will bring more fruitful outcomes than simply going with the flow.

Retirement is full of uncertainties:

- How much money will I need?

- How long will I live?

- What rate of return will I get on my investments?

These days, retirees can expect to live up to thirty or so years in retirement. It can be stressful thinking about how you will structure your time and money for your life post-work.

The aim of this guide is to equip you with the knowledge and tools to deal with the uncertainties and have a fabulous retirement.

Choose the retirement you want

Some people let life happen to them while others decide what they want and find a way to make it happen. The latter approach is based on the premise that you have a choice. Obviously it is not unlimited, but you do have the choice to use your available time and money for the things that matter most to you.

The starting point for your retirement plan is to clearly identify what is important to you. It might be:

- Travel.

- Spending time with family and friends.

- Hobbies such as gardening, photography, music, art, genealogy, or playing bridge.

- Sports – golf, running, cycling, walking, bowls, petanque, tennis etc.

- Keeping fit – yoga, working out at the gym.

- Volunteer work in the community.

- Participating in clubs and service organisations such as Probus, Grey Power, Rotary, Lions etc.

Deciding how you want to spend your time will determine how much money you will need. For example, if you want to spend several weeks a year travelling overseas, you are likely to need considerably more money than someone who is not interested in travel. Some retirement activities are more expensive than others. You may have to pay an expensive joining fee or annual subscription as well as additional costs for meals or outings.

Then, there is the task of deciding where you want to live. You may plan a move to a different home at some point. What you spend on your retirement home may be more than your present home, particularly if the home is newer and lower maintenance, even if it is smaller. Where you choose to live will also have an impact on travel costs. If you choose to live in a retirement village, you may have to allow for the weekly or monthly service fees. If you wish to avoid going into a rest home later in life, you may need to allow for the cost of someone to come and assist you in your home.

It is not possible to plan ahead with precision over a thirty-year period, but it helps to have a broad view of what you want to achieve in the long-term while being more specific about short-term goals. Breaking your retirement into blocks of time can help you achieve a clearer picture.

Three stages of retirement

Life is a journey that has an end. We just don’t know how long it will take to get there. If you are worried about running out of money before you run out of life, the most conservative approach you can take to planning your retirement is to plan to live a long time. If you do happen to live for a shorter time than you expect, at least you won’t have run out of money! Of course, there may be issues that impact on your longevity, such as an already known health issue, or a family history of either long or short life spans. At the end of the day, you need to make a calculated guess, but make your estimate at the longer end of what you think might be your life span. If there is a big age gap between you and your partner, you will need to make sure your money lasts long enough for the younger person’s needs, without depriving the older partner of the opportunity to really enjoy their remaining time. Once you have estimated your life span, break your retirement period into blocks of time. In general, retirement has three separate stages:

|

The ‘Live it Up’ stage.This is the most active stage of retirement where money is spent on physical activities such as sport and travel, generally, just getting out and enjoying life. |

|

The ‘Fix it Up’ stage.If you upgrade your car and home décor at retirement, chances are that ten or so years into your retirement you will have to do it all over again. During this stage, you might also need to spend money on your health, for such things as hearing aids, cataract operations, or hip replacements. |

|

The ‘Wind it Down’ stage.In the final years of life, you may need to pay for someone to care for you in your home, or you may want to allow for moving to a retirement village or rest home. |

Think about how long each stage might be. This will be determined by a number of factors, such as your current age, your state of health, and how active you plan to be in retirement. If you are not sure, simply divide your estimated life span by three and adjust to suit.

Exercise 1 - Plan your retirement

Take an A4 piece of paper and turn it to a landscape orientation. Divide the page into three columns. Put a heading at the top of each column. You can use Live it Up, Fix it Up and Wind it Down, or headings of your choice that reflect three different periods of time. Under each heading write the number of years in that period. Now, fill up each column with your vision of how you will be spending your retirement in that time span. Be as specific as you can. For example:

Your financial overview

You have two types of financial resources: assets and income.

Your assets

At retirement, your assets will comprise your house (which will hopefully be debt free) and your investments (KiwiSaver and other investments). Something to keep in mind is the balance between the value of your house and the value of your investments. If all, or most, of your money is tied up in your house, you will be asset rich but cash poor. As a rule of thumb, aim to have an investment portfolio valued at about half the value of your house.

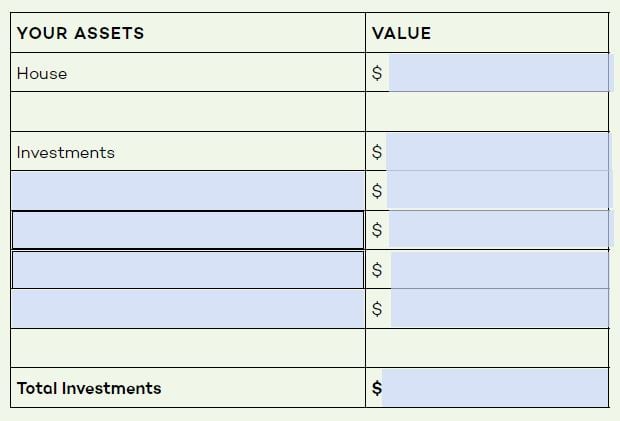

Exercise two - Where is your wealth

Write down the value of your house and the value of your investments like this:

HOW DOES THE VALUE OF YOUR INVESTMENTS COMPARE TO THE VALUE OF YOUR HOUSE?

If too much of your wealth is tied up in your house, you are in danger of being “asset rich and cash poor”. You can change this ratio by adding to your investment portfolio before you retire or, by downsizing your house.

Your Income

Your income may come from a variety of sources:

- NZ Superannuation (NZ Super)

- Other pensions, such as GSF pension, company pension, or overseas pension

- Part-time employment

- Income from investments (interest, dividends, rent etc.)

Exercise three - What will your retirement income be?

Write down your estimated annual retirement income from sources other than your investments like this:

Income & expenses bucket

There is an old saying that the best way to eat an elephant is one bite at a time. Cutting a large object into chunks always makes it easier to manage. It is no different with financial resources. The chunks need to be bite-sized; not too big and not too small, just the right size that is easiest to manage. For the purposes of this guide, we will call these chunks ‘buckets’.

If you have done the income exercise in the previous section, you will have an idea of what your retirement income will be. It may vary over time. For example, you may stop working part-time or your investment income may rise or fall. However, on an annual basis it should be reasonably straight forward to predict. Now you need to decide how to use your income to cover your outgoings. You will have two types of outgoings:

- Your ongoing Daily Living Expenses. These are usually paid for with your fortnightly income

- Lump Sum Expenses. These are one-off or irregular outgoings, such as dental care, holidays, furniture, a new car etc. These are usually paid for out of your savings or investments.

Money buckets for daily living expenses

Why is it that our grandparents seemed to be able to manage their money a lot better than we can? Last century, before the advent of electronic banking and when employees were typically paid in cash, money management was much simpler. Dad took out his money for beer and cigarettes, paid the rent or mortgage, and gave Mum the housekeeping money. Out of this, Mum would set aside a little each week to save up for new clothes (if there was any spare). She would divide up the rest into portions, often putting each portion into a separate container, to cover food, clothes for the children, power, telephone etc. Because everything was done in cash, both Mum and Dad always knew exactly how much money they had left until the next pay day.

The secret to getting your daily living expenses under control is to follow the same simple rules that our grandparents used.

Grandma and Grandpa’s golden rules for managing money

RULE NUMBER ONE

Have one “account manager” for each of your bank accounts – that way, each account is somebody’s responsibility rather than nobody’s.

RULE NUMBER TWO

Separate your personal spending from your household spending. Each partner should have their own personal account into which an agreed amount is paid each payday. This does two things – it sets a limit on the amount of personal spending but it also gives freedom to each partner to spend money without being accountable to the other partner. These personal accounts should be clearly separated from accounts which are used for household expenditure.

RULE NUMBER THREE

Separate your known payments from your variable payments. A known payment is one that you know the amount and the date of payment with certainty. A variable payment is a payment where the amount and/or the date of payment is unknown. Known payments are usually unavoidable financial commitments and they are easier to deal with than variable payments. By setting up all your known payments to come out of a separate account from your variable payments, you will avoid having dishonour fees on direct debits and automatic payments and you will have a clear limit for what is available for variable expenses.

RULE NUMBER FOUR

Don’t spend more than you have. Set limits for what you will spend from each account that you set up - personal expenses, known expenses and variable household expenses - and stick to them. Once you start going over your limit or ‘borrowing’ money from one account to top up another, you will lose control of your money.

RULE NUMBER FIVE

Monitor your cash withdrawals. Try and use electronic payment methods wherever possible so there is a record of what you have spent and where. Use cash only for personal spending on small items. Keep cash holdings in your wallet to a minimum. Set a limit for how much cash you will spend every week and only make one withdrawal of that amount each week. DON’T take extra cash out when you make a purchase by electronic funds transfer, unless it is to take out your weekly cash allowance.

RULE NUMBER SIX

Check your bank balances regularly. The best money managers are those who know exactly how much is in each one of their accounts, every day.